Shikantaza in the style of Uchiyama Roshi:

Balancing peace and progress, or understanding the significance of zazen and study in modern daily life

Life began to change in the Meiji era

Life began to change in the Meiji era

Understanding the significance of zazen and study in modern daily life is about finding the middle way between progress and peace of mind. This is not an abstract or theoretical problem. It arises directly from Uchiyama Roshi's life experience as a Japanese who was born at the beginning of the Taisho era (1912) and still has relevance for us today.

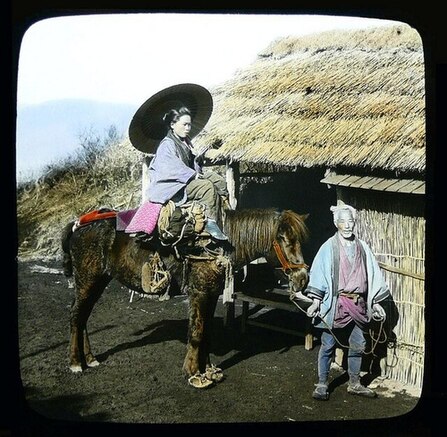

In the Tokugawa era (1600-1868), Japan was closed to outside influences, social classes were fixed, a centralized government held power, the size of the population was stable and there was little change. Fixed social classes meant that there was no competition or freedom of choice. A stable population required no advances in agriculture to feed a growing number of people. Without competition, there was peace of mind. Instead of going toward development and progress, energy went into refining the culture, increasing sophistication and elevating its aesthetics.

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan began to be influenced by Western ideas about organization and government as well as science and technology. It had to study and adopt these Western forms of progress so that it wouldn’t be left behind or swallowed up as a Western colony, but peace of mind was lost as a result.

Uchiyama Roshi witnessed the effects of this change, and this experience prompted his question: how do we find a balance between progress and peace of mind? He considered how Japan was to integrate its serene traditional culture with more driven Western development. He studied Western philosophy and Christianity as well as Buddhism in an effort to come to an understanding, and he concluded that the bodhisattva path and working hard for all beings rather than oneself was the answer. The exploration of this question of balance is the topic of his well-known book Opening the Hand of Thought. Okumura Roshi has given more than 200 dharma talks on this book and has said that he considers it his manual of practice.

Progress can encourage competition, and the result of competition is a few winners and many losers. Winners have power and money and sit at the top of the pyramid. However, Uchiyama Roshi says that there are no real winners because achieving power and money leads to suffering: fear of loss and no peace of mind. If we turn our efforts to working for all beings’ benefit and development rather than competing for our own gain, we harness the energy of our discovery, innovation and building for the creation of wholesomeness and liberation from suffering.

We live with a day-to-day tension between chasing after or escaping from things and avoiding taking any action at all in order to remain calm. Uchiyama Roshi points out that this same tension exists in our practice of zazen. While we're aiming for nonthinking, we are usually wobbling between sleeping and thinking or, as Dogen puts it in the Fukanzazengi, dullness and distraction. Shikantaza gives us the opportunity to put ourselves into the intersection of peace and progress and see what's there.

Understanding the significance of zazen and study in modern daily life isn't about applying practice as a remedy for the stress of today's busy schedule or modernizing an ancient Asian tradition to make it relevant in the modern West. It's about seeing how, in the midst of the unfolding of our own karma and the working of the causes and conditions of this moment, we can manifest the equanimity that already exists in emptiness.

In the Tokugawa era (1600-1868), Japan was closed to outside influences, social classes were fixed, a centralized government held power, the size of the population was stable and there was little change. Fixed social classes meant that there was no competition or freedom of choice. A stable population required no advances in agriculture to feed a growing number of people. Without competition, there was peace of mind. Instead of going toward development and progress, energy went into refining the culture, increasing sophistication and elevating its aesthetics.

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan began to be influenced by Western ideas about organization and government as well as science and technology. It had to study and adopt these Western forms of progress so that it wouldn’t be left behind or swallowed up as a Western colony, but peace of mind was lost as a result.

Uchiyama Roshi witnessed the effects of this change, and this experience prompted his question: how do we find a balance between progress and peace of mind? He considered how Japan was to integrate its serene traditional culture with more driven Western development. He studied Western philosophy and Christianity as well as Buddhism in an effort to come to an understanding, and he concluded that the bodhisattva path and working hard for all beings rather than oneself was the answer. The exploration of this question of balance is the topic of his well-known book Opening the Hand of Thought. Okumura Roshi has given more than 200 dharma talks on this book and has said that he considers it his manual of practice.

Progress can encourage competition, and the result of competition is a few winners and many losers. Winners have power and money and sit at the top of the pyramid. However, Uchiyama Roshi says that there are no real winners because achieving power and money leads to suffering: fear of loss and no peace of mind. If we turn our efforts to working for all beings’ benefit and development rather than competing for our own gain, we harness the energy of our discovery, innovation and building for the creation of wholesomeness and liberation from suffering.

We live with a day-to-day tension between chasing after or escaping from things and avoiding taking any action at all in order to remain calm. Uchiyama Roshi points out that this same tension exists in our practice of zazen. While we're aiming for nonthinking, we are usually wobbling between sleeping and thinking or, as Dogen puts it in the Fukanzazengi, dullness and distraction. Shikantaza gives us the opportunity to put ourselves into the intersection of peace and progress and see what's there.

Understanding the significance of zazen and study in modern daily life isn't about applying practice as a remedy for the stress of today's busy schedule or modernizing an ancient Asian tradition to make it relevant in the modern West. It's about seeing how, in the midst of the unfolding of our own karma and the working of the causes and conditions of this moment, we can manifest the equanimity that already exists in emptiness.